The Evolution of the American Nonprofit & Philanthropy (Part 1)

Here at Mockingbird Analytics, we aren’t afraid to ask the big, important questions. Questions that keep you up at night and make you really, really wonder, like:

“What’s the history of American philanthropy?”

“What was the first nonprofit in the US?”

“How did robber barons whitewash their bloody legacies by using their ill-gotten millions to create massive charitable foundations?”

Okay, so maybe those aren’t the big questions that everyone has, but if you’re anything like us, you may wonder how the American nonprofit sector grew into the trillion-dollar industry that it is today. Beyond wondering, it’s important to learn about the arc of American philanthropy because learning this history helps us better understand our place in the incredibly complex nonprofit landscape today. Something about if you don’t learn from history, you’ll be doomed to repeat it, right?

Through the nation’s history, nonprofits have emerged as key players in addressing societal needs and providing essential services to marginalized communities. But nonprofits have also had negative impacts on the very people they claimed to serve. We invite you to join us in learning more about the history of American nonprofits so that we can take these lessons from the past and apply them to the challenges that we face today. So we’re taking a dive into the past so we can apply those lessons to our work pushing the nonprofit sector in better directions.

Of course, nonprofit work is not unique to the US. Indeed, countless philanthropic and charitable organizations exist across the globe, but this article focuses on American nonprofit history, both because it is the country where we do most of our work and because it’d be very difficult to fit the history of global philanthropy into just one blog post! Other countries also have their own histories of nonprofit work to celebrate–and to reckon with–as they work towards a better future for nonprofits and the communities they serve.

The First American Nonprofits

The Pennsylvania Abolition Society historical marker

Nonprofit organizations pre-date the constitution and formation of America—though they probably would have been referred to as “charities” rather than nonprofits, as the term “nonprofit” wasn’t coined until the 20th century. One of the first nonprofit organizations in the United States was the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, which was also the country’s first abolition society! Founded in 1775, this radical and revolutionary group provided education to children who were enslaved and even campaigned to ban slavery. In 1790, the society sent their president, Benjamin Franklin, to Congress to petition for the end of slavery. Renamed as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, this organization still exists today!

Another important early nonprofit was the Peabody Education Fund, founded in 1867 through a $2 million donation from George Peabody, with the purpose of improving the state of education in the American South after the Civil War. Many consider the Peabody Fund to be the first “modern” nonprofit because it was left without restriction to a board of trustees to administer, paving the way for later nonprofits to use similar boards and practices in their disbursement of funds.

But the Peabody Fund did not serve all Southerners equally: their trustees undermined integration in the South through their prestige, influence, and most importantly, their ability to withhold charitable funds. They also required that the Peabody’s funds would only be used to improve existing schools, not new ones, which also contributed to educational segregation because most schools for Black Americans after the Civil War were new and most existing schools were segregated for whites only.

We think the Peabody Fund is an especially important example, because it is a real-life example of how nonprofits can do immense damage to communities even as they are trying to serve other communities. Yes, thousands of poor white children benefited from educational improvements, but at what cost? Wielding their funds and educational reforms like a weapon, the Peabody Fund ensured that Black Americans in the South would not have access to high quality education for decades to come.

Cultural Influences on American Philanthropy—for Better or Worse

Throughout the 1800s a distinct flavor of American philanthropy grew, influenced by factors such as religion, cultural traditions, Indigenous practices, and strategies for survival amongst settlers and immigrants in a new country.

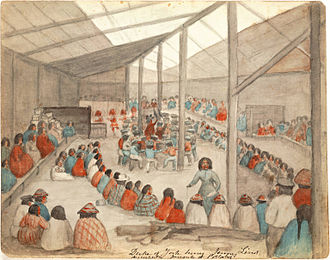

Indigenous Americans often practiced collective hunting and food distribution to ensure the health of their communities. Some Indigenous peoples, such as the Tlingit, Tsimishian, Haida, Coast Salish and the Chinook and Dene, held potlatches, large ceremonial feasts to celebrate important events. The person who hosted the potlatch gained social prestige based on how much food was served and how many gifts and possessions were given away.

A watercolor depicting a potlatch amongst the Klallam people.

White European settlers were sometimes inspired by Indigenous collective food distribution and potlatches. More frequently, they critiqued these practices as signs of poor judgment and an inclination to poverty, or they simply appropriated these practices as their own without honoring the Indigenous people who they learned them from. For most white European settlers, their ideas about giving and philanthropy were influenced by European society, which in turn was heavily influenced by Christianity, especially Puritanism, and developing capitalist economies.

Some of the more severe Puritanical beliefs that influenced settlers’ views of philanthropy was the separation of marginalized communities into the “deserving poor” and the “underserving poor.” The deserving poor were defined as those who were unable to provide for themselves due to age, disability, sickness, etc. The deserving poor existed so that those with resources to give could prove their righteousness by serving them: “thank goodness these destitute people exist so that I can prove how wonderful I am by giving them my ratty old clothes!”

The title page of Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens, a very popular book that displayed the stereotypes of the deserving poor and the undeserving poor.

The underserving poor were poor due to their own laziness and vices. The common wisdom was that the only way to help them was to remove all government and philanthropic support until they were forced to care for themselves. Only then would they reform and learn the value of hard work. A convenient argument for not providing services and resources to people you didn’t like!

This separation of the deserving and underserving poor was highly problematic(and is still a major feature of our political discourse). Hundreds of American nonprofits actively withheld their services and justified their discrimination against entire groups of people by categorizing them as underserving poor. And because the only way to “fix” them was to remove support, some nonprofits campaigned to actually decrease the few resources these groups had access to. In addition, those who were considered to be deserving poor were often fetishized for their poverty: they were only useful as far as they made philanthropists feel good about themselves. Thank goodness this kind of stuff doesn’t happen anymore, right? It’s not like as recently as 2018, then-President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers declared that poverty in America was largely eradicated and then insinuated that the only people who were still living in poverty were simply lazy and not working hard enough.

Nonprofit Progress in the Progressive Era

Let’s jump forward to the period of economic boom after the Civil War known as the Gilded Age. Rapid industrialization in America led to extreme wealth disparity. A handful of uber-wealthy businessmen, known as robber barons, wielded their power to create monopolies, influence government, and squash movements for workers’ rights. Again, thank goodness this kind of stuff doesn’t happen anymore, right?

A political cartoon showing several robber barons floating on a raft carried on the backs of workers.

The crises of the Gilded Age led to the moral, political, social, and economic reforms of the Progressive Era during the first two decades of the 1900s. This was a time defined by a wide range of reforms: women’s suffrage, prohibition, child labor laws, trust-busting, labor reform, and increased regulation in the banking and food industries.

During the Progressive Era, a number of robber barons decided to turn their attention from business to philanthropy. John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Mellon, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, Leland Stanford, and others spend the last decades of their lives focused more on giving away money than making it. Some even saw themselves as thought leaders in the philanthropic movement, such as Andrew Carnegie, who wrote “The Gospel of Wealth” and other articles that argued that–and we’re just paraphrasing here–society needed the rich to get richer so that the rich could use their wealth to improve society. Hi, Reagan, and those pesky trickle down economics!

While these businessmen’s focus on giving stimulated a wave of philanthropy across the US, many saw their turn to philanthropy as a cynical strategy to whitewash their legacies so they would be known as generous businessmen, not cold-blooded robber barons. After all, robber barons were known for ruthlessly breaking up worker strikes through violence and deadly means, as well as risking the health and safety of both their workers and the community in pursuit of profit. Elon Musk would have fit right in!

Many of the foundations that these businessmen created still exist today, such as the Mellon Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation, to name a few. These were the next developments in the history of nonprofits: large foundations with the means to grant millions of dollars in funding annually. This would permanently change the American nonprofit landscape, as nonprofits now had the chance to secure large grants from foundations in addition to the fundraising from individual donors. But this almost meant that large foundations had more control over nonprofits, as they could refuse much-needed funds to nonprofits whose work they didn’t agree with.

What’s Next?

This article is already pretty long, so we’re going to stop there–don’t worry, we’ll cover more of the history of nonprofits in America in our next installment! We enjoyed going on this journey through nonprofit history with you! Like history itself, the history of nonprofits is a complex mixture of good and ill and everything in between. Today, it’s important for us to appreciate the history of the nonprofit sector we can work in so that we can learn from the successes of the past and avoid repeating the failures.

Of course, there’s no one right way to do nonprofit work! But the more knowledge that we have about the system that we’re working in and how it got to be this way–including the nonprofit industrial complex that we all work under (more on this in the next installment!)–the better strategies we’ll be able to create to ensure that we are being responsible to the communities we aim to serve.

NEXT UP:

The Roots of Fundraising for Nonprofits

SOURCE LIST

https://independentsector.org/resource/health-of-the-u-s-nonprofit-sector/

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-american-abolition-society-founded-in-philadelphia

https://philanthropynewyork.org/sites/default/files/resources/History%20of%20Philanthropy.pdf

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/amazon-anti-union-spending-2022_n_6426fd1fe4b02a8d518e7010

https://nonprofithub.org/a-brief-history-of-nonprofit-organizations/

Read our interview with Founder & CEO of The Color of Excellence®️, Brittany Gail Thomas, Esq.! Interested in gaining new skills and knowledge for your nonprofit organization? Join our Incubator Program (more information in the article)!